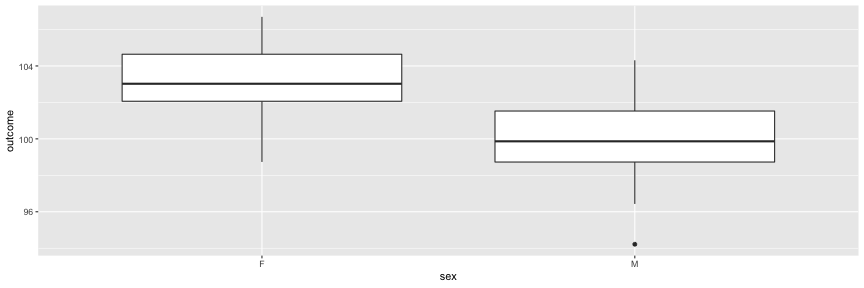

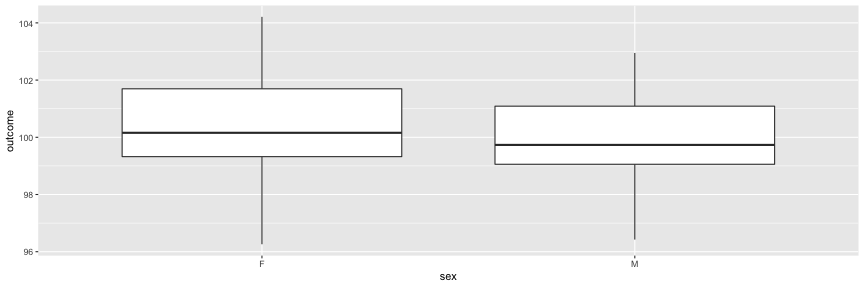

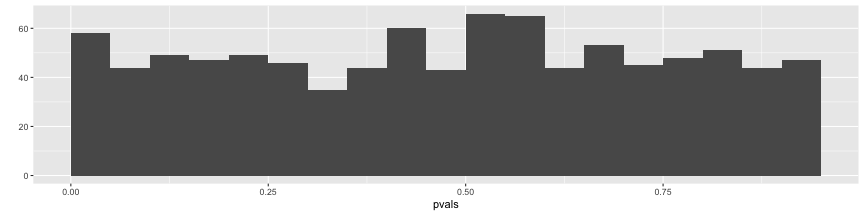

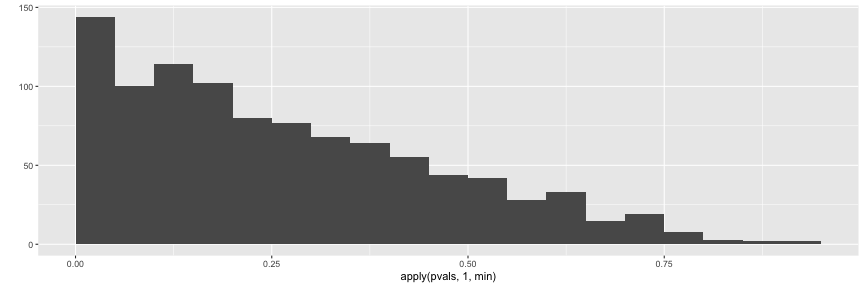

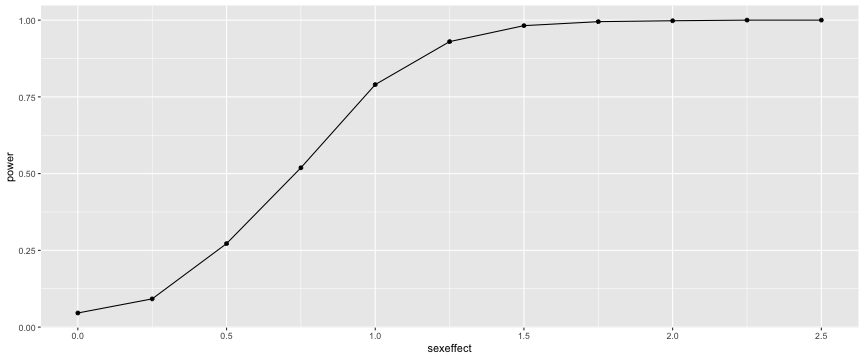

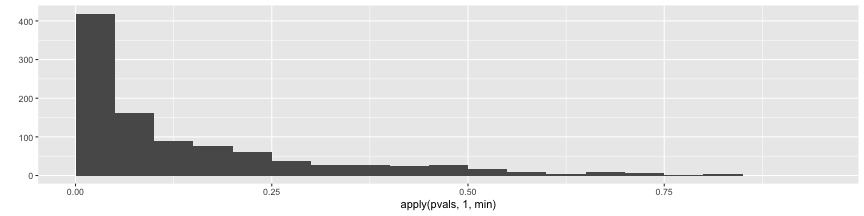

class: center, middle, inverse, title-slide # Truth and replicability ## Day 4 ### Jason Lerch ### 2018/09/13 --- <style> .small { font-size: 65%; } .medium { font-size: 80%; } .footnote { font-size: 75%; color: gray; } .smallcode { } .smallcode .remark-code { font-size: 50% } .smallercode { } .smallercode .remark-code { font-size: 75% } </style> # Hello World Today is about truth and replication, multiple comparisons, and effect sizes and statistical power. -- First, a preview of tomorrow's presentation and exam --- # Presentation No need for any extra slides - the rmarkdown document that you have been working on all week is all you need. Each group will get one or two questions (with a potential follow-up). Sample question: "Team Gelman, you said that hippocampal volume is dependent on the genotype of the mice. Can you show me, and summarize, your graphs and statistical tests to support that?" --- # Exam 9 questions that are very similar to what you've seen in the quizzes. There might even be a repeat. 1. 3 questions on either explaining what a plot (boxplot, histogram, etc.) means or providing a critique of a plot. 1. Given a linear model summary output, interpret or provide a value based on the output 1. 2 questions on long run probability, p value, monte carlo simulations. 1. Machine learning question on test, training, and validation sets. 1. Given a density plot of a prior and of data/likelihood, what would you expect the posterior to be? 1. Interpret a Bayesian linear model output. 5 questions on truth, replicability, and statistics. --- class: smallercode # A simulation function ```r simFakeData <- function(intercept=100, # what happens at age 20 in G1 M sex_at_20=3, # how F differs from at age 20 G2_at_20=0, # how G2 differs from G1 at age 20 G3_at_20=0, # how G3 differs from G1 at age 20 delta_year=0.5,# change per y for G1 M sex_year=0, # additional change per y For F G2_year=0, # additional change per y for G2 G3_year=0, # additional change per y for G3 noise=2) { # Gaussian noise age <- runif(120, min=20, max=80) group <- c( rep("G1", 40), rep("G2", 40), rep("G3", 40)) sex <- c(rep(rep(c("M", "F"), each=20), 3)) outcome <- intercept + ifelse(sex == "F", sex_at_20, 0) + ifelse(group == "G2", G2_at_20, 0) + ifelse(group == "G3", G3_at_20, 0) + (age-20)*delta_year + ifelse(sex == "F", (age-20)*sex_year, 0) + ifelse(group == "G2", (age-20)*G2_year, 0) + ifelse(group == "G3", (age-20)*G3_year, 0) + rnorm(length(age), mean=0, sd=noise) return(data.frame(age, sex, group, outcome)) } ``` --- # Simple group comparison: sex ```r library(ggplot2) library(broom) suppressMessages(library(tidyverse)) fake <- simFakeData(sex_at_20 = 3, delta_year = 0) lm(outcome ~ sex, fake) %>% tidy ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 2 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 103. 0.246 419. 5.19e-189 ## 2 sexM -3.16 0.348 -9.06 3.27e- 15 ``` --- # Simple group comparison, sex ```r ggplot(fake) + aes(sex, outcome) + geom_boxplot() ``` <!-- --> --- # Now assume no group difference ```r fake <- simFakeData(sex_at_20 = 0, delta_year = 0) ggplot(fake) + aes(sex, outcome) + geom_boxplot() ``` <!-- --> --- # Keep the output ```r tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex, fake))$p.value[2] ``` ``` ## [1] 0.1614415 ``` --- # And repeat for multiple simulations ```r nsims <- 1000 pvals <- vector(length=nsims) # keep the p values for (i in 1:nsims) { # for every simulation, compute the linear model and keep p value pvals[i] <- tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex, simFakeData(sex_at_20 = 0, delta_year = 0)))$p.value[2] } ``` What number of those p values will be < 0.05? --- # Null hypothesis ```r sum(pvals < 0.05) ``` ``` ## [1] 58 ``` ```r qplot(pvals, breaks=seq(0.0, 0.95, by=0.05)) ``` <!-- --> --- # Same null data, more complicated model ```r tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex + group, simFakeData(sex_at_20 = 0, delta_year = 0))) ``` ``` ## # A tibble: 4 x 5 ## term estimate std.error statistic p.value ## <chr> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> <dbl> ## 1 (Intercept) 99.6 0.337 296. 8.62e-169 ## 2 sexM 0.179 0.337 0.532 5.96e- 1 ## 3 groupG2 0.455 0.413 1.10 2.72e- 1 ## 4 groupG3 0.639 0.413 1.55 1.24e- 1 ``` --- # And repeat for multiple simulations ```r nsims <- 1000 # 3 tests (M vs F, G2 vs G1, G3 vs G1), so 3 outputs pvals <- matrix(nrow=nsims, ncol=3) for (i in 1:nsims) { # at each simulation, save all 3 p values. Ignore intercept pvals[i,] <- tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex + group, simFakeData(sex_at_20 = 0, delta_year = 0)))$p.value[-1] } ``` In how many of the simulations will any one of the p-values be less than 0.05? --- # Multiple comparisons Across the simulation results, check in how many simulations any one (or more) of the 3 p values that were kept was less than 0.05. ```r sum(apply(pvals, 1, function(x)any(x < 0.05))) ``` ``` ## [1] 144 ``` ```r qplot(apply(pvals, 1, min), breaks=seq(0, 0.95, by=0.05)) ``` <!-- --> --- # Dealing with Many Tests - If you're testing a lot of hypotheses, a 5% chance of making a mistake adds up - After 14 tests you have a better than a 50/50 chance of having made at least one mistake - How do we control for this? - Two main approaches Family-Wise Error Rate (FWER) control and False-Discovery Rate (FDR) control. --- # FWER - In family-wise error rate control, we try to limit the chance we will at least one type I error. - Best known example: Bonferroni correction. Divide your significance threshold by the number of comparisons, i.e. with two comparisons p<0.05 becomes p<0.025. - Quite conservative, so in neuroimaging and genetics we tend to use False Discovery Rate control. --- # FDR - Instead of trying to control our chances of making at least one mistake, let's try to control the fraction of mistakes we make. - To do this we employ the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure. - The Benjamini-Hochberg procedure turns our p-values in q-values. Rejecting all q-values below some threshold controls the expected number of mistakes. - For example if we reject all hypotheses with q < 0.05, we expect about 5% of our results to be false discoveries (type I errors). - If we have 100's or more tests we can accept a few mistakes in the interest of finding the important results. --- # Statistical power through simulations In this simulation, rather than keeping the two sexes always the same, we simulate an increasing amount of sex difference, and run 1000 simulations for every one. ```r nsims <- 1000 sexeffect <- seq(0, 2.5, by=0.25) pvals <- matrix(nrow=nsims, ncol=length(sexeffect)) effects <- matrix(nrow=nsims, ncol=length(sexeffect)) for (i in 1:nsims) { for (j in 1:length(sexeffect)) { fake <- simFakeData(sex_at_20 = sexeffect[j], delta_year = 0) l <- lm(outcome ~ sex, fake) pvals[i,j] <- tidy(l)$p.value[2] effects[i,j] <- tidy(l)$estimate[2] } } ``` --- # Statistical power through simulations ```r power <- colMeans(pvals < 0.05) qplot(sexeffect, power, geom=c("point", "line")) ``` <!-- --> --- class: smallercode # A quick power analysis using parametric assumptions ```r power.t.test(n=60, delta=0.5, sd=2, sig.level = 0.05) ``` ``` ## ## Two-sample t test power calculation ## ## n = 60 ## delta = 0.5 ## sd = 2 ## sig.level = 0.05 ## power = 0.2736564 ## alternative = two.sided ## ## NOTE: n is number in *each* group ``` ```r rbind(sexeffect, colMeans(pvals < 0.05)) ``` ``` ## [,1] [,2] [,3] [,4] [,5] [,6] [,7] [,8] [,9] [,10] [,11] ## sexeffect 0.000 0.250 0.500 0.750 1.00 1.25 1.500 1.750 2.000 2.25 2.5 ## 0.046 0.092 0.272 0.519 0.79 0.93 0.982 0.995 0.998 1.00 1.0 ``` --- # Effect size and effect found ```r esteffect <- vector(length=length(sexeffect)) for (i in 1:length(sexeffect)) { esteffect[i] <- mean(effects[pvals[,i] < 0.05,i]) } cbind(sexeffect, esteffect) ``` ``` ## sexeffect esteffect ## [1,] 0.00 0.1227268 ## [2,] 0.25 -0.7935697 ## [3,] 0.50 -0.9288426 ## [4,] 0.75 -1.0054051 ## [5,] 1.00 -1.1369201 ## [6,] 1.25 -1.2873977 ## [7,] 1.50 -1.5189690 ## [8,] 1.75 -1.7533084 ## [9,] 2.00 -2.0070775 ## [10,] 2.25 -2.2384651 ## [11,] 2.50 -2.5055891 ``` --- # p hacking ```r nsims <- 1000 pvals <- matrix(nrow=nsims, ncol=4) for (i in 1:nsims) { fake <- simFakeData(sex_at_20 = 0.5, delta_year = 0) pvals[i,1] <- tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex, fake))$p.value[2] pvals[i,2] <- tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex, fake %>% filter(group == "G1")))$p.value[2] pvals[i,3] <- tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex, fake %>% filter(group == "G2")))$p.value[2] pvals[i,4] <- tidy(lm(outcome ~ sex, fake %>% filter(group == "G3")))$p.value[2] } ``` --- # p hacking ```r colMeans(pvals < 0.05) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.276 0.128 0.120 0.123 ``` ```r sum(apply(pvals, 1, function(x)any(x < 0.05))) ``` ``` ## [1] 419 ``` ```r qplot(apply(pvals, 1, min), breaks=seq(0, 0.95, by=0.05)) ``` <!-- --> --- # Hypothesis testing and truth A p value only makes a statement about the likelihood of an event under the null hypothesis. -- To make a statment of the truth of an event, you need to know the prior probability of it being true. -- `\(P(\textrm{significant}|\textrm{false}) = 0.05\)` - the false positive rate, standard p value threshold `\(P(\textrm{significant}|\textrm{true}) = 0.8\)` - the power of the test. -- Need to know the base rate of true results in the field. If we set it to be 10%, then: `$$P(\textrm{true}|\textrm{significant}) = \frac{P(\textrm{significant|true}) P(\textrm{true})}{P(\textrm{significant})}$$` ```r (0.8*0.1)/((0.8*0.1)+(0.05*0.9)) ``` ``` ## [1] 0.64 ```